On This Day - Moss and Jenkinson Win the Mille Miglia at Record Speed!

- 1 May 2019

- On This Day

By Paul Jurd

By Paul Jurd

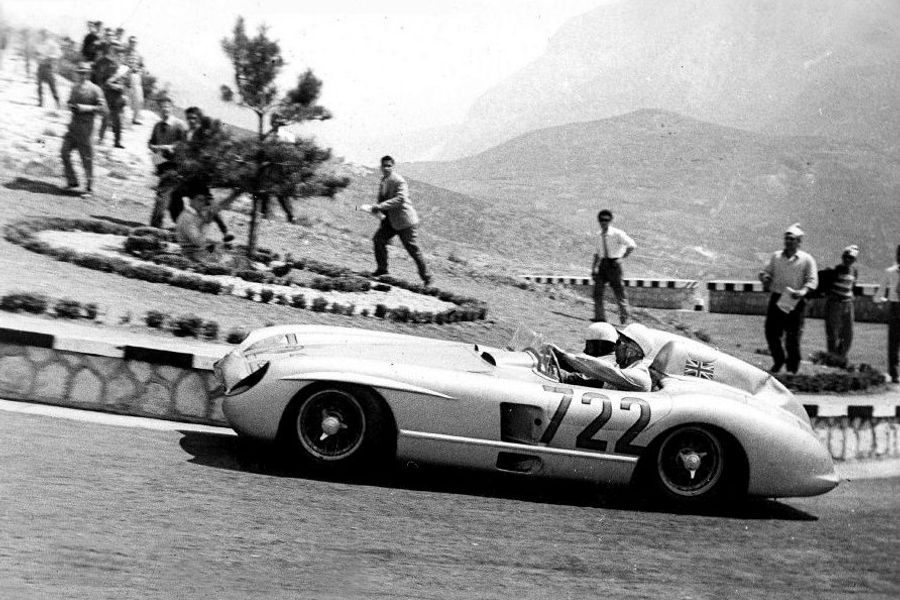

May the 1st 1955 is an auspicious day in motorsport, the day that Stirling Moss and Denis Jenkinson won the Mille Miglia in a record time, covering the 992-mile route in ten hours, seven minutes and 48 seconds – an average speed of 98.5mph. Driving a potent Mercedes-Benz 300SLR, the duo developed one of the first ever pace note systems to navigate the public roads from Brescia in North Italy to Rome and then back, heading home team-mate Juan-Manuel Fangio by half an hour and the third placed Ferrari of Umberto Maglioli by 45 minutes.

One of the most high-profile events of the period, the Mille Miglia was run as a time-trial rather than a race, with cars being set off at one-minute intervals. The 1955 event saw 661 cars start, with the slower entries being waved off first – so the first cars actually started late in the evening of April 30th. The race number of a car indicated its start time, so the Moss and Jenkinson 300SLR bore the number 722 and started at 7.22 on the morning of the first.

Mercedes-Benz were debuting the new 300SLR and had a strong line up with Moss, Fangio, Hans Herrman and Karl Kling all driving, Aston Martin sent a DB3S for Peter Collins and a brace of DB2/4s, driven by Tommy Wisdom and Paul Frere, while Ferrari had four factory cars entered. The new Mercedes were the class of the field, using the same engine as the Grand Prix winning W196 delivering around 300bhp, the cars had a space frame tubular chassis , five speed gearbox, double wishbone front suspension, and drum brakes.

Mercedes-Benz were debuting the new 300SLR and had a strong line up with Moss, Fangio, Hans Herrman and Karl Kling all driving, Aston Martin sent a DB3S for Peter Collins and a brace of DB2/4s, driven by Tommy Wisdom and Paul Frere, while Ferrari had four factory cars entered. The new Mercedes were the class of the field, using the same engine as the Grand Prix winning W196 delivering around 300bhp, the cars had a space frame tubular chassis , five speed gearbox, double wishbone front suspension, and drum brakes.

Moss was always one for extracting every advantage from a situation and in contrast to some of his team-mates, elected to have a co-driver in the car with him. He chose journalist Denis Jenkinson, a man who had watched Moss race more times than most, and was likely to stay calm in the car given that one of his pastimes was being a passenger in motorcycle sidecar races.

The pair decided that key to success would be knowledge of the route, and over several reconnaissance runs they put together extensive and detailed pace notes. Mercedes-Benz developed an intercom system for Jenkinson to relay information to Moss, but they hit an unexpected problem with the system.

It worked well initially but they quickly discovered that when cornering the car right on the limit, Moss was so focused that he was no longer aware of Jenkinson’s voice in his ears. However, his vision remained pin sharp and they evolved a set of hand signals that he could still register and react to at speed.

The notes themselves were in a box with two rollers and Jenkinson would wind them from one to the other (the rolls contained 17 feet of notes…) and it is noticeable in pictures of the race that Jenkinson is usually looking down into the cockpit, ready to feed Moss the next signal. The system worked really well, evening out their disadvantage to drivers with ‘local’ knowledge of the Italian roads, reputedly one of the rare errors was a missed note for a hump back bridge, which legend has Moss hitting at full speed and the Mercedes being launched almost two hundred yards down the road before landing again.

Early in the race it was the Ferraris at the front, Eugenio Castellotti quick early on, but setting a pace his car could not survive, before Piero Taruffi went ahead, averaging 130mph on the run down to Pescara in his 118 LM. Moss was right on the pace of Taruffi though, and a quicker stop saw him take the lead and set the quickest time as they turned inland and reached Rome.

Mille Miglia superstition said that whoever led at Rome would not win overall, but Moss was not to let that hamper him, and it was his rivals who began to falter. Kling retired after an accident just outside Rome, Taruffi was now suffering with transmission and oil pump issues, which saw him retire after half-distance, and Fangio had an injector problem on his engine.

The Futa Pass was always a testing section of the route and Herrman crashed there, moving the new Maserati 300S of Cesare Perdisa into second, only to retire on the final section from Bologna to Brescia with gearbox failure.

Moss and Jenkinson took a famous win ahead of Fangio and Maglioli, while fourth was the two litre Maserati of Francesco Giardini, an hour clear of the rest his class and a performance that Jenkinson declared one of the finest individual drives in the history of the race. With the winners recording a time just over ten hours, the other class winners where still one the road or coming in, a 350cc Isetta taking its sub-class in a time almost double that of the winners.

The Mille Miglia was an event we can only today imagine in its full pomp. A major sporting event in Italy, it was over almost one thousand miles of public roads, spectator lined in the cities, towns and villages of the lengthy route, with straw bales providing protection in case of an accident.

And…accidents did occur, even in 1955 spectators were killed, including one child, with the cars capable of 170mph blasting by and it taking just one misjudgement for a driver to spear off the event was always on a knife edge. The end came two years later in 1957, when just as crowds at the finish were starting to celebrate a popular win for Taruffi, news came in of an incident back down the route.

Alfonso de Portego was in a 3.8 litre Ferrari 315, and was running in fourth place when he had a tyre fail when flat out. The car left the road, destroyed a granite marker, a telegraph pole…then hit a line of spectators. De Portego, navigator Edmont Nelson and nine spectators were killed, five of them children, and the Italian government moved to ban racing on the road. Though that ban was later lifted for some events, it was the end of the Mille Miglia in its classic format – an event where the cars had outgrown the roads and the format.

Popular Articles

-

January 2026 Podcast: Auction Round Up, 2026 Anniversaries and the Amazing Life of Whitney Straight13 Jan 2026 / Podcast

-

December Podcast: Book Month as the Team Suggest some Stocking Fillers from Santa6 Dec 2025 / Podcast

December Podcast: Book Month as the Team Suggest some Stocking Fillers from Santa6 Dec 2025 / Podcast -

November Podcast: Jim Clark, the Man, the Museum and the Greatest Season in Motorsport11 Nov 2025 / Podcast

November Podcast: Jim Clark, the Man, the Museum and the Greatest Season in Motorsport11 Nov 2025 / Podcast -

October 2025: Romain Dumas - Le Mans Winner and Historic Ace!3 Oct 2025 / Podcast

October 2025: Romain Dumas - Le Mans Winner and Historic Ace!3 Oct 2025 / Podcast